The disease, originally known as “Macaw Wasting Disease”, was initially reported in the late 1970’s in the U.S. and Europe. The term “Proventricular Dilatation Disease” was given to the disease in a 1983 report describing “impaction, dilation, and degeneration of the proventriculus”.

The new term for this disease is Avian Bornaviral Ganglioneuritis (ABG) which is an immune-mediated disease.

As many as one-third of the avian population in captivity and in the wild test positive for the Avian Bornavirus (ABV). ABV does not appear to be zoonotic; humans and animals do not contract this infection from pet birds.

It causes disease in the class Aves which includes many species of birds. The ones with the highest number of positive results are cockatoos, Amazons, eclectus, African greys and macaws. Quakers and lovebirds have been minimally represented. Those with the lowest number are cockatiels, budgerigars, pionus, and conures.

It can be transmitted both horizontally (bird to bird) and vertically (from hen to egg), the latter is now considered to be the primary cause of transmission in birds.

ABG had previously been regarded as carrying a high-mortality but low-infection risk. In the last few years, it has been shown to occur much more frequently but involve a “low incidence of clinical disease and a much lower incidence of severe disease”. New treatment protocols have moved this disease to a more chronic state and one which often responds to treatment. Nevertheless, an infected bird will never eliminate the viral infection.

Most viruses are spread by cell-to-cell contact, first invading and destroying the host cell, then moving on to infect more cells. Borna Disease Virus does not destroy the cell, so infected cells suffer very little damage. Additionally, the virus has developed several methods to avoid being recognized by the host immune system.

ABV is a neurotropic virus, which means it attacks the central, peripheral and autonomic nervous systems. In some birds, only slight changes in behavior are noted whereas others can suffer severe neurological disease which results in fatal infections. Avian Bornavirus has been found in tissues of the brain, gastrointestinal tract, plasma, liver, lung, kidney, spleen, eye and adrenal glands of infected birds.

Unweaned birds are more vulnerable to ABV infection than adults. The estimated incubation period is between two and four weeks or longer. Hormonal and reproductive activity often gives rise to new cases and relapses of previous cases. The disease cycles from active to dormant states, and the stresses of this increased hormonal state depress the immune system, allowing clinical disease to flare up.

Figure A. |

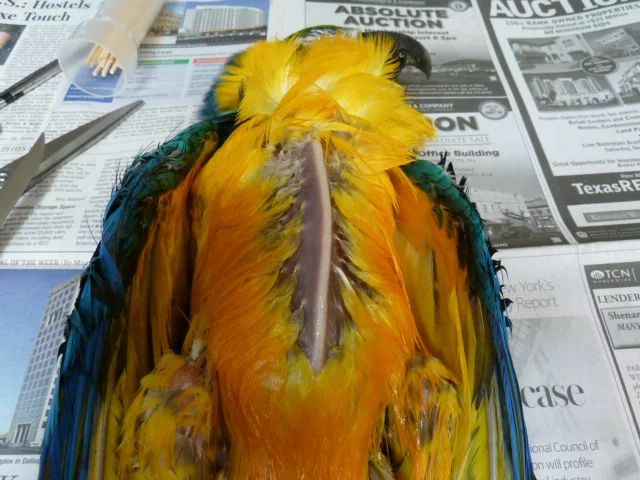

Figure B. |

| Both images above are post mortem images of very thin birds that “suddenly passed away” and they both presented looking the same. Figure A. is from an African Grey parrot that was chronically obstructed with a foreign body. She kept chewing and swallowing threads from her cage cover that was used in the evenings until food couldn’t get past the obstruction and died from “starvation”. Figure B. is from a Blue & Gold macaw that had Avian Bornaviral Ganglioneuritis “PDD” and also died from starvation because his stomach stopped working and he was unable to absorb nutrients. |

Clinical signs include:

|

Birds with CNS lesions may display:

|

| It can also attack the myocardium (heart muscle) causing myocarditis (inflammation of the heart muscle). Lesions have also been found in the conduction pathways of the heart, causing sudden death in birds which previously appear normal. It is also responsible for disorders of the eyes, leading to blindness. In the case of cortical blindness, the eye is functioning properly, but the nerves between the eye and the brain have become infected. In most cases, the eyes respond to correct treatment.

How do we test for ABG?

One drawback to both imaging and crop biopsy is that they must be performed when the bird is displaying advanced clinical signs.

How do we treat ABG? Treatment protocols and proper care are extending the lives of many birds affected with Avian Bornaviral disease. Without treatment, it is usually fatal. We use a combination of medications to help decrease the inflammation caused by the virus. In birds with gastrointestinal signs we also use medications to enhance motility and prevent secondary infections. In cases where there is self-mutilation, seizures, and neurological/neurogenic pain we add specific drugs to help with pain and control seizures. We also use hormone suppression therapy for managing hormonal increases which occur with the onset of breeding activity. We also offer Omega fatty acids to reduce inflammation. Herbal supplements like silymarin (milk thistle) are part of our liver support formula which are helpful in reducing inflammation, preserving hepatic function, and improving GI tract transit. The liver is often affected by the bacteria coming from the abnormal intestinal environment. Recommendations to Owners: Long-term survival does not mean that the bird has been cured. It still carries the virus and is a potential source of transmission to your other birds . To minimize the chances of spreading within the home or aviary, please follow these recommendations:

If you have any further questions please give us a call to schedule an appointment so our exotic veterinarians can guide you with the best diagnostic and treatment options for your bird(s). Information adapted from the paper Understanding “Avian Bornaviral Ganglioneuritis” by Jeannine Miesle M. A., M. Ed |

About Us

Our exotic animal hospital is dedicated exclusively to the care of birds, exotic small mammals, reptiles, and even fish! We can offer everything your pet needs for a healthy and happy life, from wellness care and grooming to diagnostics and dentistry, but we can also provide emergency care during our opening hours, along with more specialized treatment for referred patients.